The end of political stability in Europe

A changing system...

Standing on the verge of a new world order, we are experiencing radical change in Europe, too. The era of major parties and the resulting clear political relations in the EU member states appears to be over. Neither social democrats nor conservative people’s parties are now the driving force in Europe. Previously, majorities from one of these political groupings – beyond the 15 heads of government – set the tone alternately on the European Council (and consequently on the EU Commission). But now, volatility reigns, and governing coalitions of three or even more parties (as in the case of Italy at the moment) are becoming the norm.

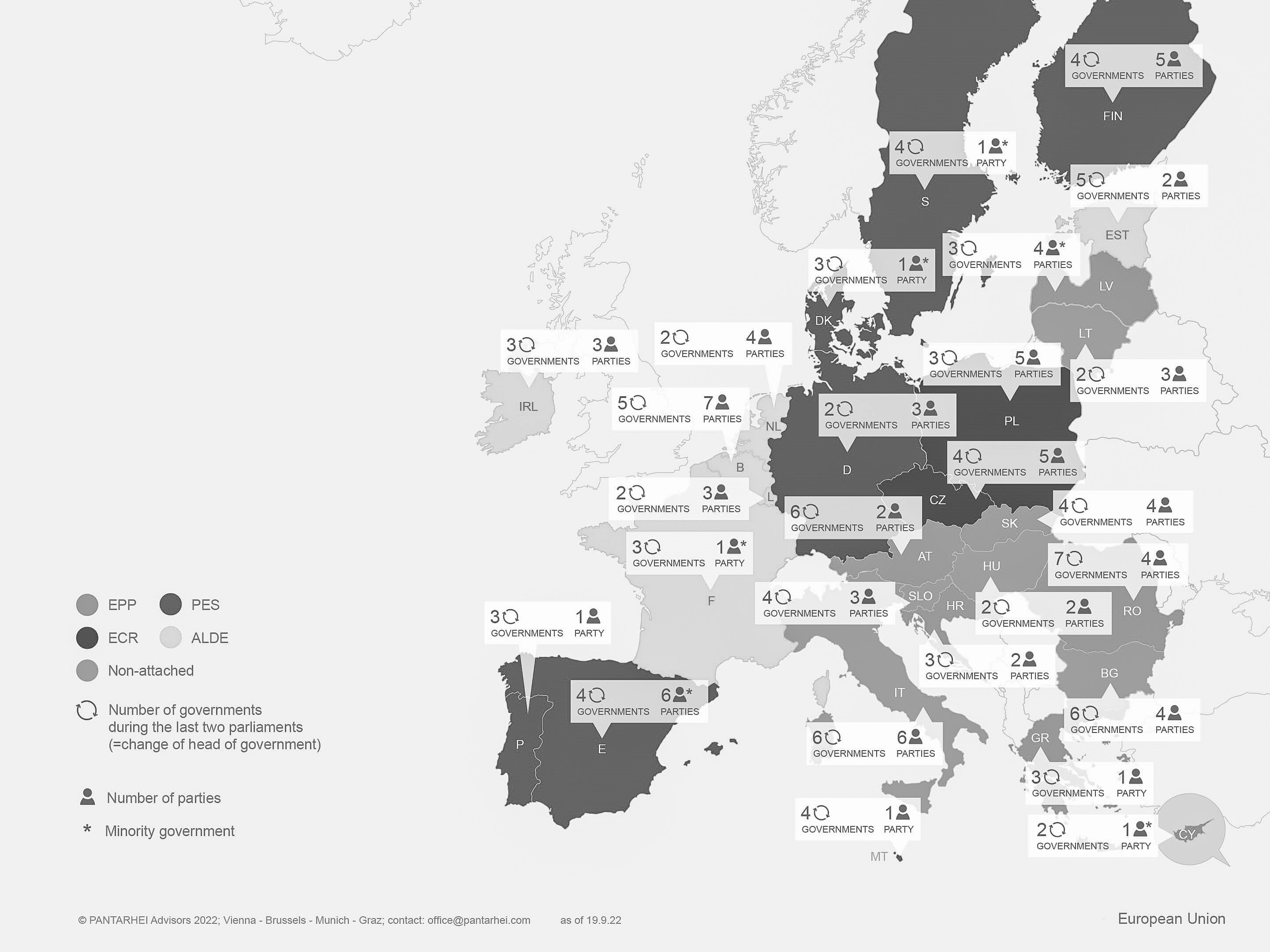

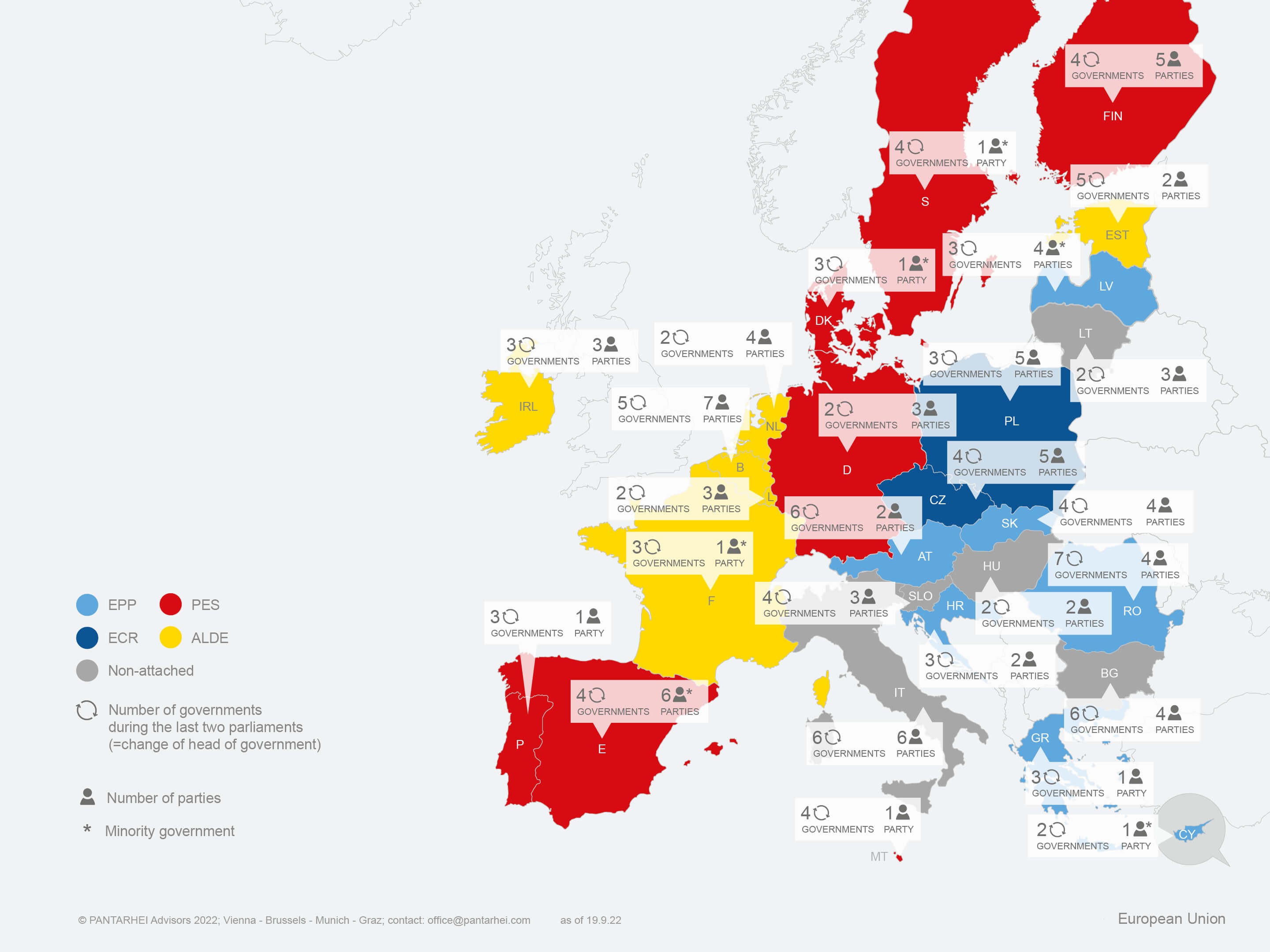

At present, 16 EU member states are ruled by coalitions comprising three or more parties. Generally speaking, this involves a former major party protecting a fragile majority with the support of smaller splinter parties. There are also five member states where the government does not have a parliamentary majority (France being the most prominent example). In addition, the ruling government has only managed to complete its last two terms in office in six of the 27 member states.

This shows that stable governing constellations with conventional majorities are increasingly becoming a thing of the past – Denmark, Ireland and Poland have each had three governments during the last two terms, while various EU states have had four, and Bulgaria and Austria have even racked up six. But Romania and Italy have the dubious honour of heading the list with seven.

...and its consequences

This fragmentation and volatility have had dramatic consequences:

- When it comes to the major overarching questions that need to be resolved – from the future of Europe and how to deal with the war in Ukraine to the EU’s geopolitical role in competition against other systems – the picture is no longer uniform.

- The Franco-German axis is not the driving force behind key European issues any more, while other alliances such as Visegrad and the Frugal Four have (for the time being) stalled at the top level.

- (Small) parties on the fringes of the political spectrum are kingmakers for former major parties – a coalition-building approach that is causing volatility and leaving parties in permanent election mode. By necessity, this is increasing the temptation to provide populist responses to complex questions.

As a result of these kingmakers, which are often small parties from the periphery of the democratic spectrum , national governments are vulnerable to blackmail and in constant danger of being toppled. This leaves us permanently in electioneering mode, and facing a revolving door of political representatives. It also means that politicians from different EU states are not in a position to build trust-based, resilient, long-term relationships. But this is fundamentally important when it comes to building up a cohesive picture and making complex decisions.

The next two years will be an even greater stress test for the EU system. It can be assumed that Russia will throw its support behind sympathetic parties in EU countries – just as it influenced the US presidential elections in 2016 – in the interests of its war in Ukraine. Looking ahead to the EU elections in 2024, and against the backdrop of soaring energy costs and inflation, a scenario in which we see the rise of radical forces at the expense of the political middle ground is becoming increasingly realistic.

What does all this mean for public affairs at the EU level

The political stage has a long history of constant comings and goings. Which translates into the need – from a public affairs standpoint – for organisations to constantly get to grips with shifting majorities and new political actors.

But the current level of instability is unparalleled. The heterogeneity in the structure of the European Council makes it seem easier to block decisions, but woe betide anyone who tries to build a majority.

One of the winners of this development is the EU Commission, which is assuming new responsibilities (with some being transferred to it by the Council as well). Taking its cue from the communitised approach to vaccine procurement, the Commission is looking to expand this model to other sectors and products (such as arms and firefighting aircraft).

For organisations and corporations in their role as corporate citizens, this is also extending their duties in terms of strengthening our democratic values and models.

The oft-cited EU labyrinth is not getting any smaller; on the contrary, new paths (and blind alleys) are being added to it. But stability and clarity are not the order of the day. The political system at the EU level is currently being rebuilt.

Here you can download our EU-Paper

Die Zukunft des

Lobbying Whitepaper